Our new NorthStandard site is now live. There will be no new content or updates added to this site. For the latest information, please visit our new site north-standard.com.

Decarbonisation in shipping: Overview of the regulatory framework

News & Insights 11 November 2021

The effects of climate change demand that environmental issues remain a high priority.

In 2015, the Paris Agreement on climate change was agreed by parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It entered into force on 4 November 2016. Its goal is to keep global temperature rise below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and preferably limited to 1.5°C.

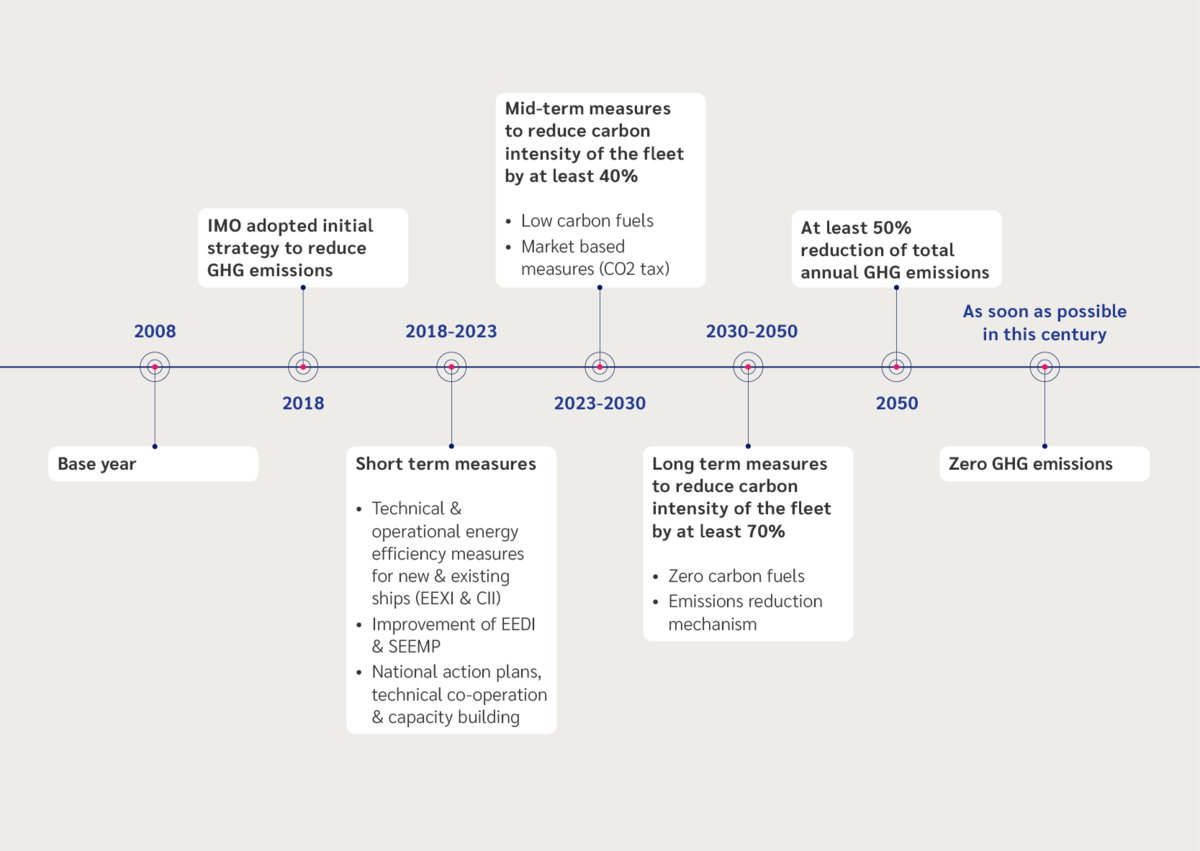

Even though the Paris Agreement does not include international shipping, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) committed to contribute its efforts to address climate change features prominently in its strategic plan. Consequently, in April 2018, IMO adopted an initial strategy on the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) from ships, i.e. emissions including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), expressed in CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent).

The IMO’s initial strategy envisages:

- to reduce total annual GHG emissions from shipping by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008, while pursuing efforts towards phasing them out entirely within this century.

2008 is the baseline year against which future reduction targets are assessed, while 2050 represents an important milestone in the Paris Agreement, which the IMO explicitly references in its strategy. These ambitions are to be accomplished by a blend of measures applicable in the short, medium, and long-term.

This publication provides an overview of the short-term measures that have been recently adopted by the IMO as amendments to the MARPOL Annex VI, requiring ships to take a technical and operational approach to reduce their carbon intensity. The mid- and long-term measures are likely to require a high degree of innovation and to result in the global uptake of new fuels and new technologies. The club will cover these aspects as the industry evolves.

Shipping emissions

The focus of maritime sector was drawn to air emissions in 1997, when air pollution was included in MARPOL as Annex VI. For the first time, limits were set on main air pollutants contained in ships exhaust gas, including sulphur oxides (SOx) and nitrous oxides (NOx), and prohibiting deliberate emissions of ozone-depleting substances.

MARPOL Annex VI, which came into effect on 19 May 2005, also regulates shipboard incineration and the emissions of volatile organic compounds from tankers. This annex has undergone several amendments to reflect the increased focus on reducing ship emissions, for example, on 1 January 2020 a 0.5% sulphur content limit in the fuel oil used on board ships came into force, marking a significant milestone to improve air quality.

Even though shipping is considered to be one of the most energy efficient modes of mass transport, it was estimated to have contributed about 2.2% to the global emissions of CO2 in 2012. As sea transport continues to grow in tandem with world trade, it is imperative to have a global approach to further improve the energy efficiency and effective emission control of the maritime sector.

According to the fourth IMO greenhouse gas study, which was published in 2020, the GHG emissions of total shipping (international, domestic and fishing) have increased from 977 million tonnes in 2012 to 1,076 million tonnes in 2018, a 9.6% increase. Over the period from 2012 to 2018, the carbon intensity of shipping operations improved by about 11%, but these efficiency gains were outstripped by growth in activity. If changes are not made, shipping emissions are projected to increase by up to 50% until 2050 relative to 2018 despite further efficiency gains, as transport demand is expected to continue to grow.

The seventy-fifth session of the IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC-75), held in November 2020, approved the findings of this study and measures to reduce GHG emissions from international shipping were deliberated. Consequently, in June 2021, MEPC-76 adopted amendments to MARPOL Annex VI to reflect the technical and operational goal-based measures to reduce the carbon intensity of international shipping.

IMO Regulations: The International Context

The IMO has been actively engaged in a global approach to enhance ship’s energy efficiency and develop measures to reduce GHG emissions from ships.

The first major step to reduce these emissions was announced in 2011, when the IMO adopted mandatory measures to increase energy efficiency of international shipping. This paved the way for the regulations on Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) for new ships, and Ship Energy Efficiency and Management Plan (SEEMP) – a ship-specific document that provides a mechanism to help improve the energy efficiency of a ship in a cost-effective manner. These mandatory measures (EEDI/SEEMP) entered into force on 1 January 2013, while targets to improve design efficiency (EEDI) of new build ships commenced in 2015.

For new ships, the EEDI requires that energy efficiency is improved in phases such that CO2 emissions are progressively reduced:

- During phase one, running from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2019, the EEDI requires a 10% reduction of carbon intensity below the relevant reference line for newly built ships.

- In phase two, running from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2024, the EEDI requires up to 20% reduction of carbon intensity.

- Phase three of the EEDI, due to commence in 2025, requires an additional 10% reduction, i.e., ships being built in 2025 will be required to be 30% more carbon efficient than those built in between 2000 to 2010.

However, during the MEPC-75, it was decided to move forward the effective date of phase 3, from 1 January 2025 to 1 April 2022, for containerships, large gas carriers (15,000 DWT and above), general cargo ships, LNG carriers and cruise passenger ships having non-conventional propulsion. A carbon intensity reduction requirement will apply to containerships, starting with 15-30% reduction rate for small container vessels and increasing up to 50% for large containerships (200,000 DWT and above). There are also considerations to introduce fourth phase of EEDI in 2027.

In addition to above, since 2019, under the IMO Data Collection System (IMO-DCS), ships of 5,000 GT and above must collect and report data on fuel consumption under SEEMP Part II. These ships account for close to 85% of CO2 emissions from international shipping. The data collected will provide a firm basis on which future decisions on additional measures will be made.

The European Union (EU) has also implemented similar regulations on monitoring, reporting, and verifying fuel consumption (EU-MRV) for ships of 5,000 GT and above calling at European ports. While IMO-DCS is an anonymous public database, the EU-MRV is a distinctive public database.

More recently, during the MEPC-76 meeting in June 2021, amendments relating to technical and operational measures to cut the carbon intensity of international shipping were adopted. These amendments will enter into force on 1 November 2022, and include the following:

- calculation and verification of Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) – retroactive EEDI requirements applied to existing ships from 1 January 2023;

- introduction of a rating mechanism (A to E) linked to the operational Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), taking effect from 1 January 2023; and

- enhanced Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) to include targets for operational emissions, where an approved SEEMP needs to be kept onboard from 1 January 2023.

a) Technical Measures: Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI)

Similar to the EEDI, the aim of the EEXI is to measure ship’s energy efficiency based on its design and arrangements. This regulation is applicable to all existing ships of 400 GT and above falling under MARPOL Annex VI. The revised MARPOL Annex VI include new regulation 23 (attained EEXI) and 25 (required EEXI).

Ships to which the regulation applies will be required to calculate EEXI value of each individual ship (i.e., attained EEXI) and the value shall be equal to or less than the allowable maximum value (i.e., required EEXI). As such, it is required to develop an EEXI Technical File, which includes the data used for calculation and will be used as a basis for verification of compliance.

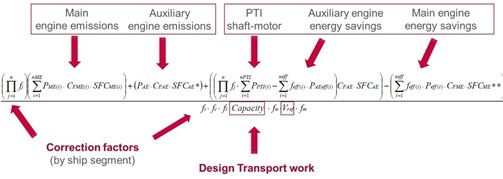

Essentially, the EEXI describes the carbon emissions per cargo ton and mile. It determines the standardized CO2 emissions related to installed engine power, fuel oil consumption and a conversion factor between fuel and the corresponding CO2 mass. The transport work is determined by capacity, which is usually the deadweight of a ship and the ship speed related to the installed power. The calculation does not consider the maximum engine power, but for most ship types it is 75% of the rated installed power (MCR), or in case where overridable power limitation is installed it is 83% of the limited installed power (MCRlim). Specific fuel oil consumption of the main engine and ship speed are regarded for this specific power. There are different correction factors that apply, depending on the ship type and capacity.

For ships where the calculated (or attained) EEXI is greater than the required, there will be a need to implement countermeasures to improve its efficiency index. Being a technical or ‘design’ efficiency index, this may include alterations to the ship’s design or machinery, such that:

- the numerator of the EEXI formula will decrease (normally action may be taken on power of main and/or auxiliary engines),

- the denominator of the EEXI formula will increase (normally action may be taken on capacity or ship’s speed).

Some of the available options are:

- introduction of an engine power limitation or shaft power limitation

- increasing ship capacity (by increasing the deadweight (DWT) or gross tonnage (GT), if structurally possible)

- propulsion optimization devices, e.g., high efficiency propellers, propeller boss cap fins, Mewis duct, low friction paints, air lubrication systems, etc.

- energy efficiency technologies (EETs), such as., waste heat recovery, wind assisted propulsion, solar cells, etc.

- switching to carbon-neutral fuel, but this might not be viable for most existing ships due to very high capital expenditure (CAPEX).

The regulations are not prescriptive on which improvement method should be deployed and the right solution may vary based on ship type and size. It is vital to consider the ship’s age against the cost and payback time of improvement option.

To facilitate the process of EEXI calculation, it is recommended that the following ship documentation is readily available:

- Capacity plan or lightweight certificate

- Trim & stability booklet

- Sea trial report

- NOx technical files of A/E and M/E

- IAPP certificate

- EEDI technical file (if available)

If suitable data cannot be obtained from these documents, techniques may be used to bridge the gap such as statistical (conservative) estimates, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations or, if necessary, sea trials.

The EEXI Technical File will need to be approved by the ship’s Flag State or Class and the compliance with the EEXI regime will be reflected in the International Energy Efficiency Certificate (IEEC) at the first annual, intermediate or renewal survey of the International Air Pollution Prevention (IAPP) certificate on or after 1 January 2023 for ships delivered before 1 January 2023, or at the initial survey of IEEC for ships delivered on or after 1 January 2023.

b) Operational Measures: Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) and enhanced Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP)

The CII is an operational measure applicable to ships of 5,000 GT and above, which aligns with the requirements on recording ship’s fuel consumption in accordance with the IMO Data Collection System (IMO-DCS).

As per the revised MARPOL Annex VI regulation 28, from 2023 applicable vessels will need to:

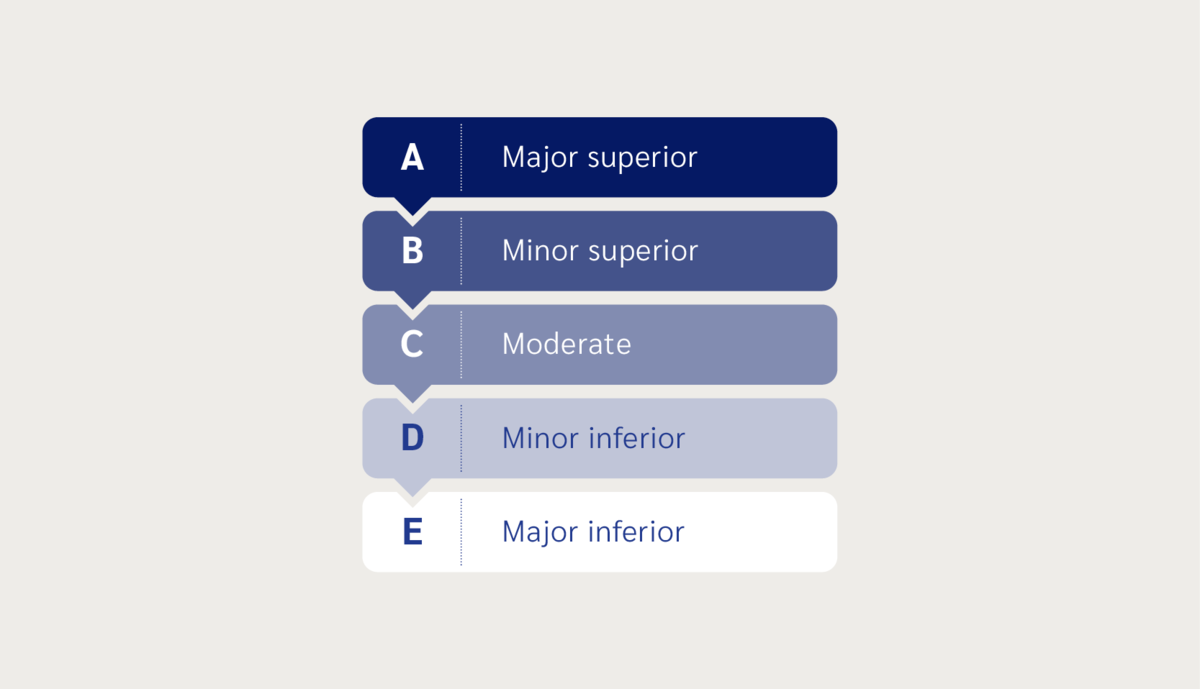

Ships will be given an annual carbon intensity rating (CII rating) indicating their performance over the previous year. There are five CII rating categories given on a scale from A to E, where A is the best, based on a calculation of Annual Efficiency Ratio (AER) or capacity gross ton distance (cgDist).

AER (emission per dwt-mile) is used for the majority of ship segments where the cargo is weight critical, while cgDist (emissions per gross ton-miles) is used for volume-critical cargo, like cruise ships, vehicle carriers roll-on/roll-off (Ro-Ro) and roll-on/roll-off passenger (ROPAX) vessels.

The attained annual operational carbon intensity indicator will be based on IMO-DCS. Emissions data must be submitted through the IMO-DCS in addition to the existing fuel consumption requirement. Emissions reporting must, as a minimum, include the AER (for bulk carriers, tankers, container ships, general cargo, LNG carriers, gas carriers, combination carriers and reefers) or the cgDIST (for passenger cruise ships, vehicle carriers, Ro-Ro and ROPAX).

As required by the MARPOL Annex VI regulation 26, an enhanced version of the SEEMP will need to be developed. This would include:

- the ship’s CII rating together with the description of the methodology used to calculate the ship’s attained annual operational CII,

- the required annual operational CII for the next three years,

- an implementation plan documenting how the required annual operational CII will be achieved during the next three years, and

- a process for reporting to Flag State for verification.

From 1 January 2024, ships will be issued with a Statement of Compliance (SoC), covering verified fuel consumption, attained carbon intensity reduction and an annual rating (A to E) based on carbon intensity reduction performance against the required carbon intensity reduction. Ships rated ‘D’ for three consecutive years or at rating ‘E’ for one year, will have to submit and implement a corrective action plan showing how they can improve the vessel's efficiency to ‘C’ or above. The corrective action plan is to be included in the SEEMP.

Periodic SEEMP verification audits will be introduced to ensure plans are in place to achieve the targets and ensure correction plans are being followed where a ship is rated E in any given year, or D in three consecutive years. The frequency and specific requirements of these audits is expected to be discussed at MEPC-77 in November 2021, with guidance developed in 2022.

In addition to the above, the MEPC-76 approved a phased approach of 2% carbon intensity reduction as compared to the 2019 reference line from 2023 (when the MARPOL amendments would enter into force) through to 2026 (when another review to further strengthen the annual reduction rate is due to take place):

Year | Annual reduction factor (from 2019 reference) |

2023 | 5% |

2024 | 7% |

2025 | 9% |

2026 | 11% |

2027-2030 | Still to be decided |

If regular improvements are not made, a ship’s CII rating could drop as the targets will become increasingly strict every year. A consequence of this could be loss of earnings and inability to trade, so there is a strong incentive to improve energy efficiency.

European Union (EU) Proposal: “Fit for 55” Package

In addition to the IMO regime, the EU has set itself a target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 – commonly known as ‘European Green Deal’ under the European Climate Law. To get there, the current GHG emission levels need to drop substantially over the next decades. Consequently, the EU has raised its 2030 climate ambition, committing to reduce GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels.

On 14 July 2021, the European Commission adopted 'Fit for 55' package that consists of 13 proposals – four of them are aimed to accelerate efforts to decarbonise shipping. Some of these proposals have drawn concerns and criticism as they could potentially undermine IMO’s efforts on decarbonisation and increase vessel’s administrative burden.

The proposed revisions on the EU climate legislation would need to be approved by the European Parliament and the EU Council before turned into law. Once approved, the EU “Fit for 55” initiative, is anticipated to have significant implications for EU and non-EU ship operators and the global bunker supply industry.

The four proposals which have the most direct impact on the maritime sector and bunkering are dealt with below.

a) Revision of the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS).

The EU-ETS is based on the 'cap and trade' principle. A cap is set on the total amount of certain greenhouse gases that can be emitted by the ship and is reduced over time so that total emissions fall. Under the EU-ETS, shipping companies will have to purchase and surrender emission allowances to cover each tonne of carbon generated on voyages or else face potential penalties from EU port authorities for non-compliance. The fine in terms of emitting more CO2 compared to the emission allowances is expected to be at least 100 euros per excess tonne.

Under the proposal, implementation of the EU-ETS to the shipping industry could start as early as 2023 and phased in over a three-year period. It applies to ships of 5,000GT and above, regardless of flag and involves:

- 100% of the emissions when calling at an EU port for voyages within the EU,

- 50% of the emissions from voyages starting or ending outside of the EU, and

- emissions that occur when ships are at berth in EU ports.

The shipping company is required to calculate and report the aggregate emissions on an annual basis as follows:

- 20 % of verified emissions reported for 2023

- 45 % of verified emissions reported for 2024

- 70 % of verified emissions reported for 2025

- 100 % of verified emissions reported for 2026 and each year thereafter

It is anticipated that a ship failing to comply with the revised legislation and failing to pay the penalty may be detained by port authorities or even denied the entrance to a port. Additionally, the names of companies in breach of the EU-ETS scheme could be made public.

For more information on the EU-ETS please see here. The recent Carbon Market Report published by the Commission can be found here.

The key target of this proposition is to promote the use of sustainable fuels by addressing:

- market barriers that hamper their use,

- uncertainty about which technical options are market ready.

This initiative focuses on all ships of 5,000 GT and above, regardless of their flag, calling at an EU port. The targets are determined against a reference value reflecting the fleet average greenhouse gas intensity of energy used on-board by ships in 2020, and reduced by the following percentages:

- 2% by 2025

- 6% by 2030

- 13% by 2035

- 26% by 2040

- 59% by 2045

- 75% by 2050

This initiative sets a limit on the GHG intensity of fuels used onboard from 2025 onwards and imposes an obligation on containerships and passenger ships to use on-shore power supply from 2030 unless they can demonstrate use of alternative zero-emission technology while at berth. There is an exemption for ships that:

- are at berth for under two hours;

- using zero emission technologies;

- have to make an unscheduled call at a port for safety reasons; and

- are unable to hook up to shore power because of non-availability.

c) Energy Taxation Directive (ETD)

This proposal introduces a new structure of tax rates, and the removal of tax exemptions, on marine fuels sold within and for use within the EEA starting from 2023.

Essentially, the new rules lay down a minimum excise duty rate on the relevant fuels used for intra-EU ferry, fishing, and commercial ships with a view to encourage a switch to more sustainable fuels used by ships trading within EU.

d) Alternative Fuels Infrastructure (AFI)

To support the FuelEU Maritime proposal, this initiative sets requirements for the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) maritime ports to ensure adequate liquefied natural gas (LNG) bunkering infrastructure by 2025, and to install shoreside power supply to serve the demand of at least 90% of container and passenger ships calling at that port.

Other industry developments

The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) has put forward a proposal to the IMO, calling for an internationally accepted market-based measures to accelerate the uptake and deployment of zero-carbon fuels. A levy would be based on mandatory contributions by ships of 5,000GT and above trading globally for each tonne of CO2 emitted. Funds raised from the levy would go into an ‘IMO Climate Fund’ to accelerate the development of new fuels and infrastructure. This proposal has received support from Intercargo.

The new carbon levy proposal comes on top of an existing proposal by the industry to the IMO for a USD 2 per tonne bunker fuel levy to create a USD 5 billion research fund for shipping decarbonisation. However, this remains under discussion.

The maritime finance and chartering sectors have also recognised their role in making shipping greener by creating the Poseidon Principles and Sea Cargo Charter – a framework for financial institutions and shipping interests (including charterers and cargo owners), to ensure that their interests are aligned with the targets set out in the IMO’s greenhouse gas strategy.

Conclusion

The route to decarbonisation leaves shipowners and operators with an immense task of achieving compliance by reviewing operational efficiencies such as voyage optimisation, slow steaming, technological advancements in ship design, retrofitting propulsion improvement devices and/or use of alternative fuels with a lower carbon footprint. Some of these options may require more extensive changes to a ship and greater investments. With these developments, more emphasis on uplifting the skills and knowledge of crew will be needed as well.

As some of the older vessels may not be operationally efficient, these measures may lead to regulatory-driven acceleration in demolition. On the other hand, shipowners that are planning to order newbuilds will need to start thinking about mid- and long-term targets.

As 2023 approaches, shipping companies are recommended to benchmark their fleet’s performance and fuel consumption. This will allow them to understand the technical and operational measures that are required to upgrade their existing ships to a suitable efficiency level.

List of abbreviations

AER | Annual efficiency ratio (AER) is a CII metric used for segments where the cargo is weight critical, like tankers, bulkers, etc. It is reported as emission per dwt-mile |

cgDist | Capacity gross ton distance (cgDist) is a CII metric used for volume-critical cargo, like cruise ships, vehicle carriers, Ro-Ro and ROPAX vessels. It is measured as emissions per gross ton-mile |

CII | Operational carbon intensity indicator (CII) is a measure of vessel efficiency of CO2 emitted in transporting cargo/passengers. |

CO2 | Carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the primary greenhouse gas emitted through human activities. |

EEDI | Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) reflects the theoretical design efficiency of a newbuild (built on or after 2013) ship and provides an estimate of CO2 emissions per capacity- mile. |

EET | Energy Efficiency Technologies (EETs) highlights the wide spectrum of ways to potentially reduce ship fuel consumption. |

EEXI | The Energy Efficiency eXisting ship Index (EEXI) aims to reduce CO2 emissions of existing vessels by setting minimum requirements for technical efficiency. |

EU-ETS | The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) is a cornerstone of the EU's policy to combat climate change and its key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively. |

EU-MRV | The European Union (EU) Monitoring, Reporting & Verification (MRV) |

GHG | Greenhouse Gas are gases that trap heat in the atmosphere. The primary greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and fluorinated gases. |

IAPP | International Air Pollution Prevention Certificate (IAPP) is a statutory certificate issued to a ship of 400GT and above to certify that the ship complies with the provisions of MARPOL Annex VI |

IEEC | International Energy Efficiency Certificate (IEEC) is a statutory certificate issued to a ship of 400GT and above to certify that the ship complies with the energy efficiency requirements stated under MARPOL Annex VI |

IMO-DCS | The International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted a mandatory Fuel Oil Data Collection System (DCS) for international shipping, requiring ships of 5,000 GT or above to start collecting and reporting data to an IMO database from 2019. |

NOx | Nitrogen oxides are a family of poisonous, highly reactive gases. These gases are usually produced from the reaction among nitrogen and oxygen during combustion of fuels. |

SEEMP | Ship energy efficiency management plan (SEEMP) is a ship specific plan that provides a mechanism to improve the energy efficiency of a ship in a cost-effective manner. |

SOx | Sulphur oxide emissions are mainly due to the presence of sulphur compound in the fuel. Smoke containing sulphur oxides emitted by the combustion of marine fuel will often oxidize further, forming sulfuric acid which is a major contributor to acid rain. |

UNFCCC | The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established an international environmental treaty to combat "dangerous human interference with the climate system", in part by stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. |